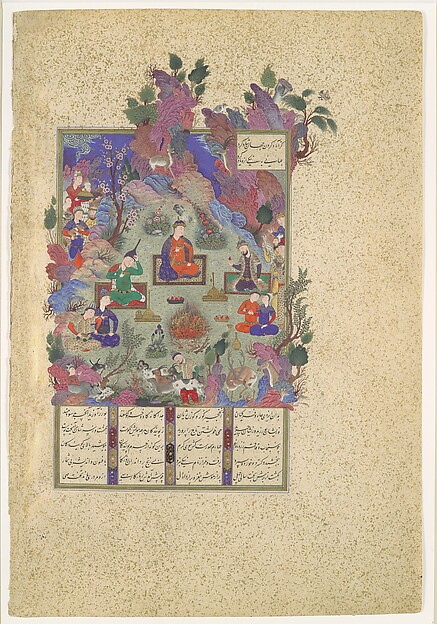

Image title: “The Feast of Sada”, Folio 22v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Medium: Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper

Date: ca. 1525

Source:

The Met Collection

“

Just as a flower, which seems beautiful has color but no perfume, so are the fruitless words of a man who speaks them but does them not.

”

— Dhammapada

Psychedelic Icons of the Islamic World: Geometry, Color, and Mysticism in Persian Miniatures

Introduction: A Mystical Kaleidoscope

In the study of psychedelic art, the colorful swirls and mind-bending patterns of the 1960s are often the starting point. But centuries before the first blot of LSD touched a tongue, artists in the Islamic world were already crafting dazzling visual experiences rooted in mystical philosophy and intricate geometry. Nowhere is this more profoundly realized than in Persian miniature painting—a tradition that flourished from the 13th through the 17th centuries and continues to inspire artists today. These paintings, though small in scale, contain vast spiritual and intellectual universes.

This blog post dives into the vibrant legacy of Persian miniatures to uncover how Sufi metaphysics, sacred geometry, and chromatic exuberance combined to form an aesthetic that anticipated modern psychedelic sensibilities. We’ll traverse the evolution of this intricate art form, from its roots in manuscript illumination to its cosmic abstraction, uncovering the spiritual and symbolic ideas that fueled its timeless appeal.

1. The Genesis of the Miniature Tradition: Mongols, Manuscripts, and Transmission

The story of Persian miniature painting begins in earnest during the Ilkhanid period (1256–1335), when Mongol rulers brought Chinese artistic techniques to Persia. With them came paper, brushwork, and a renewed interest in illustrated manuscripts. The result was a fusion of East Asian spatial sensitivity and Islamic ornamental design, giving rise to a uniquely Persian vision characterized by flat perspective, ornate details, and symbolic composition.

These early miniatures adorned scientific texts, historical chronicles, and later poetic epics like Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. More than visual decoration, they were conceptual diagrams of moral, philosophical, and religious principles—each page layered with allegory as much as pigment. The small format encouraged meditation, inviting readers into compact, gem-like worlds that demanded close scrutiny, much like a meditation mandala.

2. Geometry and the Divine: Patterns as Pathways

Islamic art long eschewed representational forms in sacred contexts, fearing idolatry. What emerged instead was an astonishing focus on geometry and abstraction. At the heart of Persian miniature aesthetics lies this philosophy: that mathematical harmony mirrors divine order. Circles, stars, and interlocking polygons weren’t just decorative—they were spiritual codes.

The conceptual backbone of this visual language was rooted in Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam. Sufis believed that the universe is a reflection of divine unity, and that through ecstatic practices one could reunite with the oneness of being. Geometric shapes in miniatures often symbolized this journey. For example, the recurring use of the eight-pointed star—created by overlapping squares—is a visual metaphor for balance between the earthly and the heavenly.

3. Chromatic Revelations: The Sacred Use of Color

Color in Persian miniatures is not merely aesthetic; it is deeply symbolic. Artists employed colors with spiritual intentionality: turquoise for transcendence, gold for divine light, lapis lazuli for celestial peace. These pigments were often sourced from rare minerals and painstakingly prepared, infusing each illustration with both physical and metaphysical richness.

Particularly during the Timurid and Safavid periods (15th–17th centuries), Persian miniature color palettes became more complex and expressive. Artists like Behzad of Herat used bold contrasts, luminous blues, and intricate textiles to create energy fields within the pictorial space, pulling the viewer into what can only be described as visual ecstasy. The rhythmic use of repeating motifs and radiant hues mirrors the synesthetic experiences often reported in psychedelic states.

4. The Spiritual Theatre: Storytelling Through Vision

Unlike Western traditions that anchored composition in realistic perspective, Persian miniatures reject linear depth in favor of metaphysical narrative. Scenes unfold not according to optical realism but spiritual logic. The viewer is encouraged to “read” the painting like one would contemplate a dream or mystical parable.

These miniatures often depict scenes from Persian literary masterworks like Rumi’s poetry or Nizami’s Khamsa, where human love becomes a metaphor for divine longing. Figures float through patterned gardens and across impossible architectures. The scenes feel suspended in time, existing outside the realm of ordinary perception—an experience echoed in psychedelic vision trips.

The page serves as a theatre of the soul, where moral struggle, existential yearning, and cosmic unity are acted out in stylized tableaux. This spiritual narrative quality resonates strongly with modern psychedelic art’s exploration of non-linear stories and inner transformations.

5. Transmission and Transformation: From Manuscript to Metaverse

Though miniature painting saw a decline during the Qajar period as European realism gained dominance, its legacy has never truly faded. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Persian miniatures have found new life in digital art, graphic novels, and even virtual reality. Contemporary artists such as Rokni Haerizadeh and Morehshin Allahyari are reviving and remixing traditional forms to explore contemporary issues.

In the West, interest in Persian miniatures surged in the psychedelic 1960s, when artists and scholars began to recognize their resonance with the expanded states of consciousness sought through acid trips and meditation. The symmetrical balance, hypnotic detailing, and symbolic storytelling offered a bridge between ancient insights and modern visual exploration.

Today, the influence of Persian miniatures can be seen not only in visual arts but in immersive tech-driven experiences. Sacred geometry animates meditation apps, while Sufi-inspired visual symphonies play across immersive projection domes. Far from being relics of the past, these miniatures are blueprints for future visual spirituality.

Conclusion: A Timeless Vision of the Infinite

Persian miniature painting reveals a profound truth: long before psychedelics entered modern consciousness, artists had already discovered how to expand perception through geometry, color, and mysticism. These works are not just art—they are spiritual tools, contemplative practices, and portals to the beyond.

By situating human experience within a vibrant cosmos of symbolic meaning, Persian miniatures remind us that the journey inward can also be a journey to the infinite. Whether viewed as proto-psychedelic visions or sacred cosmograms, they remain one of the most intricate and enchanting testaments to the spiritual power of art.

Useful links: