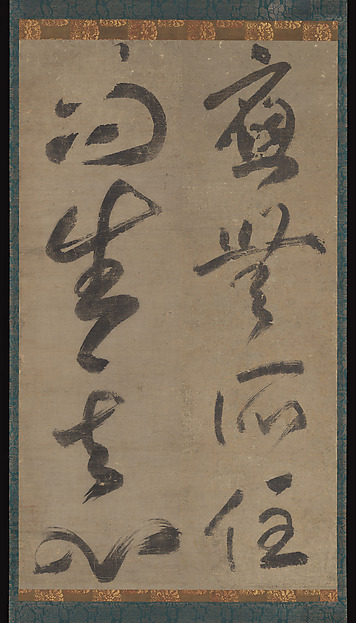

Image title: ”Abiding nowhere, the awakened mind arises”

Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Date: early to mid-14th century

Source:

The Met Collection

“

One that desires to excel should endeavor in those things that are in themselves most excellent.

”

— Epictetus

Ink That Moves: Animated Manuscripts in Islamic Calligraphy Traditions

Introduction: Animation Before Animation

Before cinema, before the flipbook, and even before the mechanical marvels of automata, animation existed—on paper, carved into architecture, and especially in ink. In Islamic calligraphy traditions, script was never merely text. It was a living aesthetic form that danced, soared, and spiraled across pages. These kinetic design principles, deeply spiritual and philosophically grounded, anticipated modern animation techniques. Within the curves and strokes lay both theological meaning and formal innovation, making them a pinnacle of sacred visual culture.

1. The Birth of Movement: Early Kufic and the Architecture of Form

The earliest Islamic manuscripts often feature the angular, monumental style known as Kufic. Though static in comparison with later cursive scripts, Kufic held its own sense of rhythm through symmetry, geometry, and balance. Letters were crafted more like architecture than lines of a text. These scripts, used primarily for Qur’anic manuscripts between the 7th and 10th centuries, embraced decorative stillness as a method of contemplation. The perceived ‘movement’ was less about optic dynamism and more about the shifting perspectives of the reader as they traveled through the parameters of sacred form. Kufic laid the foundation for the later flowering of dynamic abstraction.

2. Naskh and the Rise of Script as Motion

By the 11th century, calligraphers like Ibn Muqlah and Ibn al-Bawwab had established the six canonical scripts, of which Naskh became the most widely used. Ibn Muqlah introduced the concept of ‘al-khat al-mansub,’ or the proportional script, employing a precise geometry based on the alif (the first letter of the Arabic alphabet) and the dot unit. This standardization, paradoxically, allowed for a visual rhythm that felt kinetic. Letters flowed into each other like the currents of water, suggesting not only textual continuity but spiritual unity. As these styles matured, they became increasingly performative—less a transmission of information and more an act of visual expression.

3. Thuluth and the Dramaturgy of the Sacred

If Naskh was lyrical, Thuluth was operatic. Developed in the Abbasid era and gaining prominence under the Ottomans, Thuluth became the script of grand mosque inscriptions, imperial decrees, and intricate manuscript headings. The large, looping letters of Thuluth often seem to dance, their exaggerated curves suggesting motion caught in stillness. Unlike rigid typography, Thuluth breathes. Its theatrical flourish relies on elongation, sweep, and the illusion of physical movement—a quality that made it especially suitable for monumental inscriptions designed to engage the viewer across vast distances. Thuluth, in effect, animated the architecture it adorned.

4. Mysticism and Motion in Sufi Calligraphy

The spiritual underpinnings of animated script reached their zenith in the Sufi tradition, where the act of writing became a trance-like ritual. Scripts like Diwani and Ta’liq, with their tempestuous curves and swoonic flourishes, moved beyond textuality into esotericism. The visual movement in these scripts mirrored the whirling of dervishes or the cyclical chants of dhikr. Letters could even embody divine names or metaphysical attributes, not just through meaning but through form. The calligrapher, in this framework, became an animator of the divine word—a visual mystic projecting spiritual energy through ink.

5. The Afterlife of Motion: Legacy in Modern Digital and Visual Cultures

Although classical Islamic calligraphy looked backward in reverence to its religious source texts, its kinetic visuality opened doors to modern interpretation. Contemporary artists and designers across the Muslim world and diaspora have begun to explore the latent animation in traditional script using digital tools. Projection mapping, virtual calligraphy, and kinetic typography now rejuvenate these forms for 21st-century audiences. Far from being a relic of the past, the animated essence of Islamic calligraphy pulses within modernist abstraction as well as experimental media. Consider artists such as eL Seed or Lalla Essaydi, who recode ancient kinetic beauty for contemporary sociopolitical narratives.

Conclusion: The Pulse of the Word

The illusion of movement in Islamic calligraphy is no accident. Emerging centuries before conventional animation, it was both aesthetic and metaphysical—a visual rhythm attuned to divine frequency. As we examine these animated manuscripts today, we uncover not only historical innovations in visual communication but also a powerful reminder of art’s capacity to move us—literally and spiritually. In every inked gesture, the line becomes breath, the curve becomes echo, and the word becomes a living form.

Image description:

Ambigram Escher with two reversible hands drawing right side up and upside-down. Ambiguous image based on a symmetry of 180 degrees. Photomontage with an ambigram tessellation showing the name “Escher” in two colors using negative space upside down. M. C. Escher’s work features mathematical objects and operations including impossible objects, explorations of infinity, reflection, symmetry, perspective, and tessellations. This composition is a tribute inspired by Drawing Hands, a famous creation by Escher featuring two reversible hands drawing each other (archive).

License:

CC BY-SA 4.0

Source:

Wikimedia Commons

Useful links: