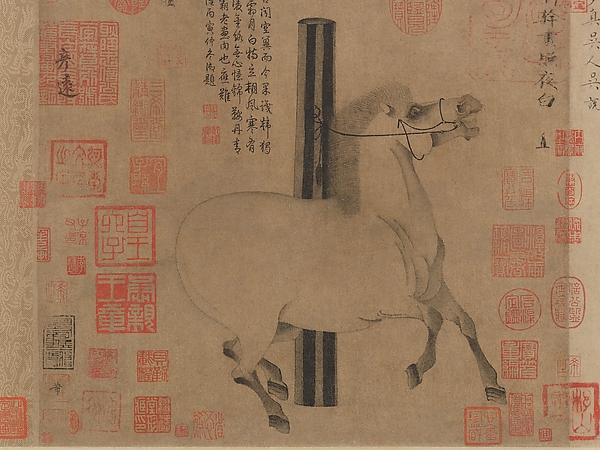

Image title: Night-Shining White

Medium: Handscroll; ink on paper

Date: ca. 750

Source:

The Met Collection

“

When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.

”

— John F. Kennedy

Ink as Rebellion: Underground Chinese Brush Painting during the Cultural Revolution

Introduction: Art in the Shadows of Revolution

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), official art was co-opted into a singular purpose: the propagation of Mao Zedong’s ideology. Traditional Chinese ink painting, once revered and intricately tied to thousands of years of cultural heritage, was condemned as feudal and counter-revolutionary. Yet in this crucible of artistic suppression, a clandestine movement was born. Using the time-honored techniques of brush painting, underground artists transformed the very materials of the past into subtle acts of rebellion. This is their story—a narrative of covert ink works that resisted the erasure of tradition and autonomy.

Chapter 1: The Cultural Revolution and the Campaign Against Tradition

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution to purge ‘Four Olds’: old customs, culture, habits, and ideas. Traditional Chinese painting, particularly works inspired by scholar-artists of the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, was labeled as decadent and counter-revolutionary. Maoist Realism, a variant of Soviet Socialist Realism, became the sanctioned style. Depictions of plump peasants, heroic workers, and radiant Chairman Mao flooded the public sphere. Art schools stopped teaching ink painting; master painters were persecuted, some publicly humiliated or even killed. Brushes were locked away, rice paper stashed in attics, and silence fell over workshops that once echoed with contemplation and the scratch of ink on silk.

Chapter 2: Ink in Exile—The Silent Practitioners

Amid this cultural repression, a quiet underground movement persisted. Risking imprisonment, artists fled to rural areas or disguised their practice under the guise of children’s calligraphy classes. Some turned to painting during the night, using hidden rooms or forested cabins as makeshift studios. They rewrote classics in secret, painting mountains and rivers not merely as landscapes but as cries for permanence against ideology’s tide. The materials themselves—ink made from soot and glue, brushes of goat and wolf hair, hand-ground ink stones—embodied a tactile reverence for continuity.

Chapter 3: Symbolism and Subversion: When Mountains Speak

Deprived of overt political language, underground brush painters turned to coded symbolism. The pine tree, evergreen and unbending, symbolized integrity. Cranes represented longevity and wisdom, outlasting ephemeral political storms. Rivers became metaphors for resilience—flowing, adapting, yet enduring. Unlike Maoist poster art, saturated in reds and bold bombast, these works whispered. Steeped in Taoist and Confucian philosophy, they celebrated introspection, balance, and harmony with nature—all values anathema to the revolution’s doctrine of struggle and rupture.

Chapter 4: Transmission Without Transmission: Keeping Ink Alive

The practice of traditional brush painting had always thrived on the intimacy of mentorship and the “heart transmission” between master and pupil. With senior artists silenced, younger practitioners became autodidacts, learning from smuggled manuals, fragments of classical texts, or by copying ancient works from memory. Ironically, technological innovation of the time—photocopying—helped circulate classical paintings in black and white among hidden circles. Through whispered referrals and coded exchanges, ink painting survived, each brushstroke a quiet act of defiance.

Chapter 5: Aftermath and Legacy: Ink Reawakens

When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, artists emerged from the shadows. While some returned to academia, others chose to transform their rebellion into renewal. The 1980s witnessed a resurgence of contemporary ink art, blending avant-garde approaches with ancient techniques. Artists like Li Huasheng and Gu Wenda, influenced by their clandestine brushes from youth, pushed the medium into new conceptual territories. Today, ink painting bridges past and future—a dialogue between philosophical stillness and modern expression. The rebellious ink of the Cultural Revolution has evolved into a canvas of remembrance, resilience, and reinvention.

Conclusion: The Power of a Brushstroke

In a time when speaking dissent could cost lives, ink painting became more than an artistic endeavor—it was a sanctuary of selfhood, a vessel for cultural memory. These unsung artists, wielding soft brushes and black ink, defied erasure with every careful line. Their legacy reminds us that true art not only reflects its era, but resists it, reimagines it, and, ultimately, survives it.

Useful links: