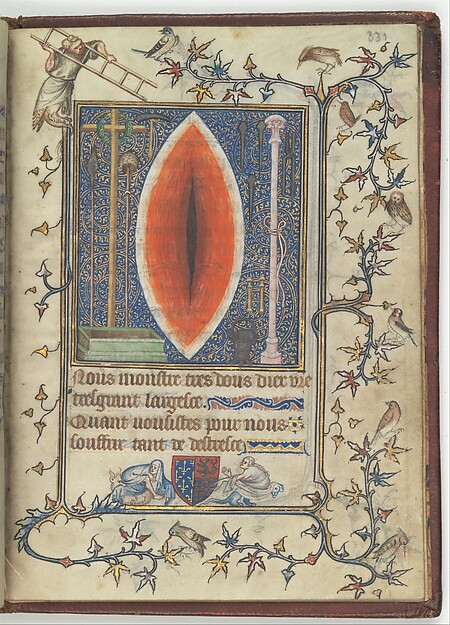

Image title: The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy

Medium: Tempera, grisaille, ink, and gold on vellum

Date: before 1349

Source:

The Met Collection

“

Gold medals aren’t really made of gold. They’re made of sweat, determination, and a hard-to-find alloy called guts.

”

— Dan Gable

Glory Holes & Gold Leaf: Queering Medieval Manuscript Margins

Introduction: More Than Marginalia

The illuminated manuscripts of medieval Europe are often admired for their shimmering gold leaf, sacred texts, and ornate calligraphy. Bound in velvet and hand-crafted in silence, these works conjure images of piety and stoic monastic life. But in the margins—beyond the illuminated initial and below the lines of scripture—there lurks another world: irreverent, bawdy, playful, and, quite surprisingly, queer. This wildly imaginative realm of marginalia challenges modern assumptions about a conservative Middle Ages and invites us to reconsider how medieval minds engaged with gender, sexuality, and the body.

Chapter 1: The Grotesque and the Erotic in Gothic Marginalia

During the Gothic period (12th–14th centuries), manuscript artists filled margins with wild creatures, hybrid bodies, and scenes of exaggerated sexuality. Far from the sacred center of the page, the margins became spaces of freedom—a medieval version of the subconscious. Phallic creatures, bare-bottomed figures, and priests in precarious positions with animals litter the tiny universes to the sides of psalters and bestiaries. The presence of these images in religious texts may shock modern audiences, but they served both as commentary and release. These erotic grotesques were not merely jokes—they expressed ambivalence about institutional control, anxieties about sexuality, and a celebration of bodily pleasures unconstrained by orthodoxy.

Chapter 2: Gender Fluidity and Playful Subversion

Many marginal illustrations subvert contemporary gender norms. Men are shown wearing women’s clothing; women wield male-coded authority or sport facial hair; and some figures defy gender categorization altogether. In a time when gender was legally and theologically rigid, the manuscript margins offered a playground for experimentation. Transgressive figures enact impossible performances—like monkeys dressed as friars or nuns in amorous entanglements with fantastical beasts—presaging queer identities that would not have explicit language for centuries. These images may not reflect overt political agendas, but they record a cultural appetite for ambiguity, mutation, and the fluidity of roles and bodies.

Chapter 3: Visual Technologies of Desire

The mediums of manuscript production—vellum, gold leaf, and natural pigments—enabled a tactile and sensuous experience for readers. One did not merely read a manuscript; one touched, smelled, and explored it. Erotic marginalia were not buried shamefully but displayed in plain sight, suggesting that their creators assumed a shared understanding or even amusement from readers. Innovations in pigment and gold leaf during this period allowed for heightened realism and sparkle—making erotic and queer images even more captivating. The presence of glory holes (often cartoonishly stylized) or exposed bodies was part of a larger visual language that embraced desire and bodily curiosity, albeit through layers of humor and allegory.

Chapter 4: Holiness and Humor: Monks, Scribes, and Queer Narratives

Much of this marginalia was the work of monks and scribes themselves—professional men immersed in scripture yet irreverently inserting images of sodomy, wild copulation, or phallic trees into religious volumes. Was this a critique of their own cloistered lives? Or a safety valve against celibate repression? The answer lies perhaps in the Catholic tradition of paradox: the sacred and profane coexisting. Medieval scriptoria were spaces where high theology met earthy labor. Queer marginalia illustrate the coexistence of doctrinal restraint and bodily fantasy. They are not accidental inklings but structured visual commentaries that allow us to glimpse how sexuality—especially non-normative sexuality—was understood, negotiated, and often laughed about in these communities.

Chapter 5: From Margins to Meaning: A Queer Art History

Modern queer theory offers new frameworks for interpreting medieval marginalia—not as outliers or ironic detritus, but as deeply embedded expressions of human experience. Scholars like Roland Betancourt and Madeline Caviness have highlighted how manuscript margins provide evidence for premodern queer imaginations. These images do not offer identity in a modern LGBTQ+ sense, but they model fluidity, challenge binaries, and foreground the performative nature of gender and desire. In queering the margins, we unearth stories that were always there—just on the edges. By embracing these flamboyant, freakish, and fabulous illuminations, we can rewrite art history not by erasing its norms, but by revealing alternative visions of beauty, sexuality, and imagination lurking just beyond the gilded frame.

Conclusion: Illuminating the Unspoken

The beguiling glow of gold leaf shouldn’t blind us to the mischievous energy of medieval margins. Underneath the solemnity of scripture and the authority of the Church, a rogue cast of phallic snails, amorous beasts, and cross-dressing saints invites us to laugh, leer, and linger. In the creative rebellion of illuminated manuscripts, queerness is not encoded—it leaps off the page with feathered wings, animal bodies, and the wink of medieval mischief. Though the language and categories of sexuality have changed, the margins remain a testament to the persistence of desire, humor, and the uncontainable queer spirit that flourishes where it’s least expected—and most needed.

Useful links: