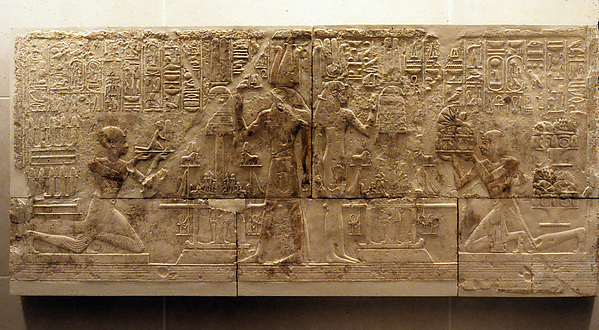

Image title: Relief from the West Wall of a Chapel of Ramesses I

Medium: Limestone

Date: ca. 1295–1294 B.C.

Source:

The Met Collection

“

Formula for success: under promise and over deliver.

”

— Tom Peters

‘Decolonize This Frame’: Museum Wall Texts Under Scrutiny

Introduction: The Quiet Power of Wall Texts

The white walls of a museum are rarely neutral. Every caption, every placard, every interpretative label tucked beside a painting or artifact carries more than just information—it carries intention. While visitors often breeze past museum wall texts as secondary to the artwork itself, these small snippets serve as powerful mediators between the object and the observer. They frame our understanding of culture, identity, and history. In recent years, a growing movement of artists, scholars, and curators has issued a clarion call to “decolonize” this curatorial language, reframing how stories are told within the hallowed halls of institutions rooted in colonial legacies.

Chapter I: The Colonial Lens in 19th-Century Institutions

The 19th century marked the golden age of museum-building in Europe and North America, deeply entwined with imperial expansion. Artifacts looted during military excursions or acquired under exploitative colonial conditions found their way into glass cases, often without reference to their violent displacement. Wall texts—when present—typically framed these objects as trophies of civilization or ethnographic curiosities. An Egyptian sarcophagus might be labeled with wonder at its age but absent of any context regarding how it left its country. These institutional narratives cemented colonial ideologies, casting the West as both the collector and interpreter of “othered” cultures.

Chapter II: Postwar Shifts and the Language of Universalism

Following World War II, museums sought to refashion themselves as temples of universal knowledge. As decolonization reshaped geopolitical maps, the curatorial language began to shift subtly. Neatly sidestepping contentious origins, institutions employed neutral, academic tones and chronological categorizations that suggested objectivity. However, the framing still privileged Western art historical paradigms—linear progress, Enlightenment ideals, and aesthetic mastery. Indigenous artworks, when shown at all, were often categorized under anthropology rather than art, denying their creators artistic agency. The wall texts thus functioned as veils, obscuring uncomfortable histories while maintaining an image of curatorial neutrality.

Chapter III: The 1980s and the Rise of Institutional Critique

By the 1980s, artists and theorists began to openly challenge the authority of museums. Entire movements—such as Institutional Critique—used art itself to question how knowledge and power are constructed. Artists like Fred Wilson rearranged exhibitions to expose historical biases embedded in display and text. Wilson’s groundbreaking 1992 project “Mining the Museum” interrogated the Maryland Historical Society’s narrative strategies, juxtaposing silverware with slave shackles to highlight erasures in institutional storytelling. During this period, wall texts grew more self-aware, acknowledging gaps and exploring multiple viewpoints. This was the beginning of a philosophical turn—curators started seeing themselves not simply as educators, but as translators and mediators whose voices needed critical examination.

Chapter IV: Decolonial Praxis in the Digital Age

The digital revolution brought new tools—and new dilemmas—for curators. Online catalogs, interactive wall texts, and augmented reality experiences granted unprecedented access but also extended the reach of potentially biased narratives. Simultaneously, scholars rooted in decolonial theory called for dismantling epistemological hierarchies. Artists from historically marginalized communities amplified this critique, refusing to be footnotes in their own stories. Exhibitions like “Unfinished Conversations” at Tate Modern began rewriting wall texts in collaboration with artists and communities, foregrounding voices that had long been silenced. This moment marked a shift from inclusion to co-authorship, reframing not only who writes the wall text, but who gets to decide what story matters.

Chapter V: Toward Radical Transparency and Plurality

Today, museums are confronting legacies of exclusion with increasing urgency. The most forward-thinking institutions are embracing radical transparency—openly stating uncertainties, acknowledging colonial histories, and welcoming multiple interpretations. Technologies like QR codes now link viewers to oral histories, curatorial dissent, and artist commentaries. Even the language of wall texts is evolving: from authoritative summaries to conversational, reflective prompts. The goal is not to erase history but to expose its layers. At the Brooklyn Museum, a wall text might read not only when an African mask was created, but also when and how it was taken, by whom, and for what purpose. Context becomes content.

Conclusion: Framing the Future

“Decolonize this frame” is more than a slogan—it is a call to see art as not just what hangs on the wall, but how it’s spoken about, who gets to speak, and whose histories are heard. As museums grapple with their roles in a post-colonial world, wall texts are becoming battlegrounds of meaning, ethics, and power. Rewriting these frames doesn’t just tell new stories—it reimagines who has the right to tell them in the first place.

Useful links: