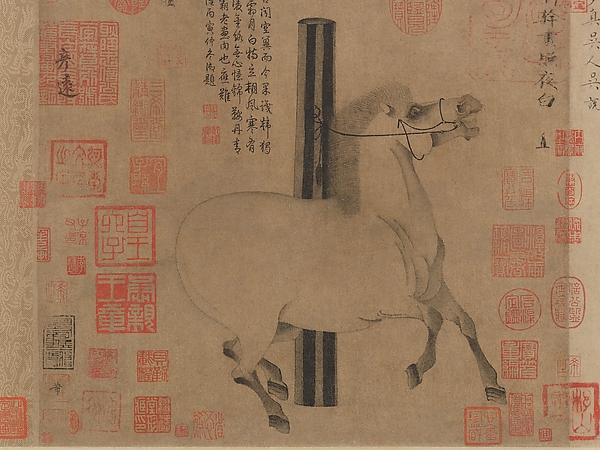

Image title: Night-Shining White

Medium: Handscroll; ink on paper

Date: ca. 750

Source:

The Met Collection

“

I am not bothered by the fact that I am unknown. I am bothered when I do not know others.

”

— Confucius

‘I Am Not Your Artifact’: Postcolonial Resistance in Museum Curation Artworks

Introduction: A New Kind of Museum Intervention

Across the grand halls of Western museums stand echoes of empires: looted artifacts, decontextualized objects, and curated narratives that reflect centuries of colonial domination. But in the 21st century, a new generation of artists is reclaiming the space—literally. Through provocative installations, performative critiques, and institutional collaborations, contemporary artists are offering potent commentaries on the traditional role of museums and the inherited violence inscribed in their collections. This post delves into the historical foundations of colonial collecting missions, follows the ascent of critical museology, and showcases how postcolonial resistance in art is reshaping museum culture from within.

1. Cabinet of Curiosities: The Roots of Imperial Display

The story of colonial artifacts in museums begins in the 16th century with the ‘Cabinets of Curiosity’ that emerged among European elites. These private collections—often filled with exotic objects brought back from conquering expeditions—were less about scholarly understanding and more about asserting dominion over distant lands. The aesthetic of wonder masked a deeper narrative: trophies of territorial conquest sanitized and exoticized into display. Collections eventually evolved into public museums, like the British Museum (1753) and the Louvre (1793), where objects from Africa, Asia, and the Americas began to be codified not through their cultural meanings, but through European taxonomies and hierarchies.

2. Enlightenment and the Myth of Universalism

During the Enlightenment, European museums placed themselves as bastions of universal knowledge. The idea that a ‘universal museum’ could represent global cultures under one roof was central to the colonial project. Philosophers like Kant and Hegel, although influential, perpetuated a Eurocentric vision of a linear historical progress—with Europe at its pinnacle and ‘the Other’ as a primitive stepping stone. Museums played an integral role in this ideological scaffolding. Art and artifacts were removed from their original communities, stripped of context, and placed into categories designed to reinforce Western superiority. The act of collecting became an extension of the civilizing mission.

3. Decolonization and the Rise of Critical Museology

The mid-20th century marked the formal end of many colonial empires, but their cultural residues lingered in museum practices. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that the field of critical museology began systematically questioning how museums narrate and legitimize colonial histories. Artists and scholars started foregrounding provenance, context, and the voices of source communities. Technological developments also played a pivotal role: databases, digital storytelling, and augmented reality tools enabled alternate narratives and restitutive visualizations. A growing movement for restitution—like France’s 2018 Sarr-Savoy Report—challenged institutions to re-examine the legality and morality of their collections. The museum was no longer an uncontested space of authority.

4. Interventions from Within: Artists Rewriting the Script

Contemporary artists have stepped into museum spaces, not only as exhibitors but as interrogators. In 2013, Nigerian-American artist Fred Wilson arranged a series of interventions at the Baltimore Museum of Art titled “Mining the Museum,” juxtaposing ornate silverware with iron slave shackles to expose the painful histories hidden in aestheticized objects. In 2018, Congolese artist Sammy Baloji conducted performative installations in European museums, using dancers and video projection to bring African agency back into rooms once filled with silence. Such works don’t destroy institutions—they problematize them. They compel viewers—and curators—to confront the contradictions between the democratic mission of museums and the oppressive origins of their most prized exhibits.

5. Toward a Postcolonial Future: Dialogical Curation and Technological Bridges

The future of postcolonial resistance in museums lies in shared authorship and digital collaboration. Projects like the International Inventories Programme (IIP), which tracks Kenyan cultural objects in Western museums, exemplify a new mode of co-curation. Technologies like VR and interactive archives now allow source communities to tell their stories in immersive ways that subvert traditional hierarchies. Artists such as Kader Attia explore trauma and repair through installations that digitally recombine fragmented cultural legacies. In embracing postcolonial approaches and technological tools, museums have the opportunity to transform from keepers of conquest into spaces of dialogue, healing, and justice. And with every intervention, one can almost hear the refrain, loud and clear: “I am not your artifact.”

Useful links: