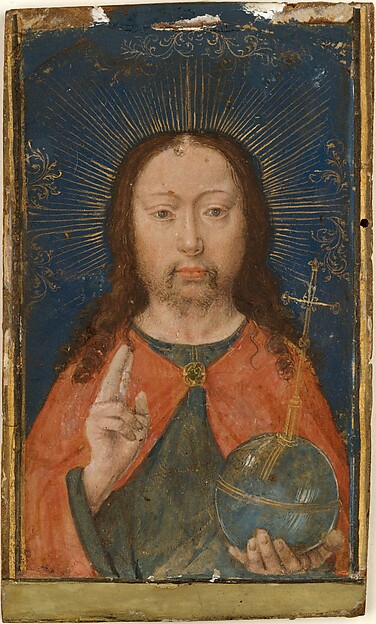

Image title: Holy Face

Medium: Tempera and gold leaf on parchment that has been trimmed and laid down on thin walnut

Date: ca. 1485–90

Source:

The Met Collection

“

”

—

“Wrong” Proportions: Disability Representation in Medieval Manuscripts

Introduction: A Reframed Perspective on Medieval Disability

In the illuminated pages of medieval manuscripts—those delicately hand-painted books that bridged the sacred and artistic worlds of the Middle Ages—we discover a surprising and often overlooked narrative: the depiction of physical difference. While modern viewers might be quick to interpret unusual bodily forms as symbols of moral failing or divine punishment, the reality is far more complex. Physical and cognitive differences in these manuscripts were not always reduced to allegory or caricature; in many cases, they were treated with nuance, dignity, and even empathy. This blog explores how disability and physical difference were visualized, contextualized, and interpreted in medieval Western manuscripts, tracing their evolution across different eras and under varied philosophical and technological influences.

Chapter 1: Early Medieval Views—From Theological Symbol to Human Experience

In the early Middle Ages (roughly 5th to 10th centuries), Christian theology significantly shaped the visual language used in manuscript illumination. One of the most well-known ideas was that of the ‘body as a reflection of the soul.’ Under this model, individuals with physical differences were often viewed as externalizations of internal sin or spiritual impurity. We see this in biblical manuscripts, such as those illustrating the parables of Christ healing the blind or infirm. However, not every representation reinforces these moral tropes. The renowned Carolingian manuscripts, for instance, occasionally depicted figures with apparent disabilities participating in daily life or canonical events—not cast out, but present with a quiet sense of belonging. This indicates that alongside theological symbolism, there was also a developing interest in representing human life in its full, unidealized range.

Chapter 2: The Romanesque Era—Grotesque Forms and Symbolic Boundaries

By the 11th and 12th centuries, Romanesque manuscript art developed a fascination with the grotesque. Marginalia—the playful or chaotic images drawn in the margins of illuminated texts—featured exaggerated human and animal forms, often in distorted proportions. While some of these figures can be interpreted as mocking or satirical, it’s critical to read them in the context of medieval humor and allegory. Physical distortion in these images didn’t always correspond with actual disability; rather, it played with notions of inversion, otherness, and the instability of meaning. Still, amidst these chaotic borders, real differences sometimes appeared too—hunched backs, lost limbs, and asymmetrical features—suggesting an awareness of corporeal variation that was not entirely abstract.

Chapter 3: The Gothic Shift—Empathy and Individualization

The late medieval period, especially from the 13th century onward, saw the rise of more naturalistic representation, in concert with the Gothic style. Figures became more individualized, faces more expressive, and bodies closer to anatomical observation. This shift was influenced by scholastic philosophy, which emphasized empirical observation and the individual’s capacity for reason and dignity. In this artistic climate, portrayals of disability began veering toward empathy. Manuscripts such as the Luttrell Psalter and the Maastricht Hours include scenes of everyday life where people with physical differences are integrated into communal life—plowing fields, knitting, or even participating in festivals. These depictions suggest neither ridicule nor moralization but rather inclusion—an acknowledgment of diversity within the human experience.

Chapter 4: Tools of Compassion—Technology, Craft, and Representation

It’s also important to consider the technological and material elements of manuscript-making. Illuminated manuscripts were intensely collaborative projects involving scribes, illuminators, and patrons. Depicting disability involved not only artistic choices but also cultural ones—what did the workshop think appropriate, what did patrons allow, and what did viewers recognize? In some cases, disability isn’t just passively recorded but is presented with striking clarity and intentionality. For instance, in depictions of the healing miracles of saints, the afflicted are painted with careful attention to crutches, missing limbs, or facial disfigurements. These details not only dramatized the miracle but acknowledged the reality of people who lived with disability. The careful rendering of such figures suggests more than narrative utility; it implies observation, familiarity, and a certain degree of compassion in representation.

Chapter 5: Rethinking the “Wrong”—Modern Lessons from Medieval Manuscripts

Our preconceived notions about progress in representation deserve reexamination when we look at medieval art. While modern society often prides itself on inclusion, the medieval world, through its illuminated pages, occasionally showed a quiet, candid recognition of difference that was not always stigmatizing. Contemporary disability studies have begun to unearth these subtleties, reading medieval images not through anachronistic pity or revulsion, but through frameworks of community, functionality, and embodied experience. These manuscripts remind us that ‘wrong proportions’ are not necessarily wrong—they are part of human variation, deeply ingrained in our visual and cultural memory.

Conclusion

Illuminated manuscripts remain vibrant witnesses to the medieval worldview, filled with beauty, contradiction, and complexity. Within their gold leaf and vivid inks, we find not just divine stories, but glimpses of how difference—bodily, cognitive, and emotional—was seen, documented, and felt. Far from mere didactic tools or moral symbols, disabled figures in medieval art emerge with a quiet resilience and, at times, a remarkable dignity. They challenge us to reconsider how we define empathy, visibility, and humanity—then and now.

Useful links: