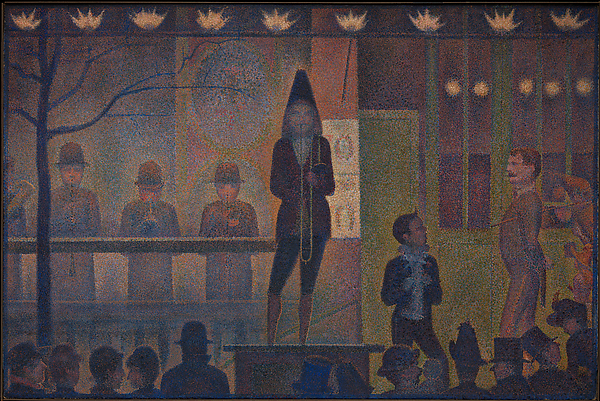

Image title: Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque)

Medium: Oil on canvas

Date: 1887–88

Source:

The Met Collection

“

The art challenges the technology, and the technology inspires the art.

”

— John Lasseter

Post-Soviet Pixels: How Digital Art Reimagined Eastern Europe’s Visual Identity

Introduction: Art After the Empire Falls

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, it didn’t just mark the end of a political hegemony—it spurred the collapse of one of the 20th century’s most robust visual coercions. Across post-Soviet Eastern Europe, artists found themselves living amid the ruins of socialist realism, the grandeur of communist iconography, and the heavy shadow of ideological propaganda. Into that fragmented silence crept a new medium: digital art. Emerging initially from underground subcultures and desktop computers, digital art became the language of a generation trying to remix, critique, and ultimately reconfigure the wreckage of their inherited identities.

Chapter 1: Collapse and Code—The 1990s Digital Underground

The early 1990s in Eastern Europe bore witness to a cultural and ideological vacuum. With government-backed art institutions either shuttered or restructured, many young artists turned to personal computers, rudimentary software, and pirated tools to spark creative rebellion. In cities like Moscow, Kyiv, and Warsaw, digital art collectives sprouted in squats and basements, fusing cyberpunk aesthetics with the leftover visual debris of Soviet iconography.

This era saw the rise of glitch aesthetics as both a practical limitation and a philosophical lens. Artists embraced digital errors—pixelation, data corruption, and compression artifacts—as metaphors for both the fragmentation of identity and the instability of truth in the region’s new reality. The glitch thus became a politicized rupture, deliberately distorting Lenin busts, Red Army visuals, and Stalinist architecture into ironic mosaics of failure and possibility.

Chapter 2: Memes, Irony, and the Language of the Net (2000-2010)

By the early 2000s, Eastern European digital artists had adopted the Internet as both canvas and community. Forums, early social media, and net.art communities allowed cross-border collaboration and rapid cultural exchange. This period was dominated by irony—an attitude born out of disillusionment and fatigue toward both Western capitalism and Soviet nostalgia. Soviet symbols were no longer just subverted—they were memeified.

Artists like Poland’s Rafal Zajko and Russia’s Olga Grotova began creating digital installations and animations that infused old communist motifs with absurdity and satire. Hammer-and-sickle icons spun into GIFs, Stalin’s face reimagined in ASCII, and propaganda posters recast with digital nonsense slogans. These works weren’t merely jokes—they were acts of counter-memorialization, distilling complex political emotions into absurd, punchy visuals.

Chapter 3: Techno-Folk and Neo-Ethnography (2010-2015)

As the digital medium matured and artists gained access to more advanced software and global platforms, a fascinating fusion arose between high-tech techniques and folkloric content. Post-Soviet artists began exploring their pre-Soviet roots through digital myth-making, creating technicolor reinterpretations of national myths, indigenous rituals, and forgotten cultural motifs.

Ukrainian artist Alina Kleytman fused 3D animation with Slavic pagan symbols, while Lithuania’s Pakui Hardware incorporated virtual sculpture and augmented reality to explore themes of body, labor, and mythology. This period witnessed digital art’s move away from pure rebellion and sarcasm, inching closer to a search for origin, belonging, and re-sacralization through technology. It was less glitch, more glitch-shamanism.

Chapter 4: The Digital Barricades—Art and Resistance Post-2014

The 2014 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea brought politics crashing back into the art spaces of Eastern Europe. Post-Soviet digital artists, already skilled in remixing political imagery, turned their focus toward resistance, documentation, and activism. Memes became weapons, and gifs became battlegrounds.

Ukrainian digital artists created augmented-reality installations to commemorate protesters killed by sniper fire. In Belarus, artist collectives responded to the 2020 protests with mobile exhibits and online archives, preserving suppressed historical truths through blockchain-anchored works. These artists had become digital archivists, cryptographic memorialists resisting erasure with every deliberate pixel.

Chapter 5: Post-Socialist Surrealism in the NFT Era (2016–Present)

The global NFT boom gave Eastern European digital artists unprecedented visibility. Artists like Dima Nova, who went viral for fusing Ethereum-based artworks with Soviet brutalist architecture, gained platforms that once seemed impossible. The crypto-art space became a surreal east-meets-west frontier, where the ghosts of Karl Marx shared blockchain space with vaporwave aesthetics and speculative art markets.

Yet, many artists remain critical of the commodification of their inherited trauma. Some use the NFT space to fund real-world activism, while others intentionally embed their work with anti-capitalist commentary—a reminder that the digital is not divorced from ideology. Instead, it has become the final arena where the post-Soviet self can misbehave, remember, resist, and rebuild.

Conclusion: A New Iconography for a Fractured Horizon

The post-Soviet pixel is more than a stylistic choice—it is a historical residue, a tool of subversion, and a language of liberation. In reprogramming the visual DNA of Eastern Europe, digital artists aren’t just archiving the collapse of one narrative; they’re authoring new ones. Through glitchy Lenin busts, technofolk avatars, and NFT manifestos, they’ve reimagined what it means to create under the shadow of buried empires—unearthing, one pixel at a time, a future as imagined and unstable as any byte-shaped revolution.

Useful links: