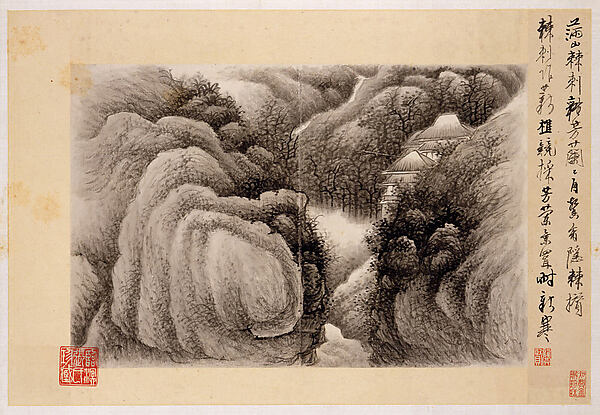

Image title: Landscapes with poems

Medium: Fifteen leaves from an album (1980.516.2a–c and 1981.4.1a–o) of eighteen leaves

Date: 1688

Source:

The Met Collection

“

Neatness begets order; but from order to taste there is the same difference as from taste to genius, or from love to friendship.

”

— Johann Kaspar Lavater

Tattooing the Gods: Sacred Ink Traditions from Polynesia to Siberia

Introduction: More Than Skin Deep

Across millennia and continents, the human body has served as a sacred vessel—both a canvas and a conduit for the divine. Among the earliest and most enduring forms of spiritual expression is the tattoo. Far from being merely ornamental, tattooing has for many cultures signified rites of passage, spiritual authority, ancestral reverence, and cosmic alignment. From the sun-drenched islands of Polynesia to the frostbitten tundras of Siberia, cultures have used ink to speak to the gods, honor the dead, and protect the living. In this article, we embark on a journey through sacred ink traditions, exploring their artistic elegance and spiritual depth.

Chapter I: Polynesian Cosmographies of Skin

Polynesia, often hailed as the spiritual cradle of tattooing, offers one of the richest ink traditions in recorded history. The word “tattoo” itself originates from the Tahitian “tatau,” meaning “to mark.” In Polynesian societies such as Samoa, Tonga, and Hawaii, tattoos are more than identity markers—they are living maps of genealogy, social roles, and metaphysical protection. Traditional tattooing was a lengthy, painful rite performed by specialist priests using handmade tools—sharpened bone combs and natural pigments—to channel mana, or spiritual power, into the body. Complex geometric patterns reflected the cosmos, oceanic travels, and ancestral legends, transforming the bearer into both a storyteller and a spiritual being.

Chapter II: The Ainu and Inked Guardianship

In Japan’s remote northern regions, the indigenous Ainu people practiced a unique spiritual tattooing tradition largely focused on women. Ainu tattooing, often found around the mouth and hands, symbolized maturity, fertility, and protection against evil spirits. Far from aesthetic, these tattoos had shamanic significance—each line warded off malevolent forces and beckoned ancestral guidance. The tattooist herself held quasi-priestly status and was integral to the community’s spiritual and cultural cohesion. Though these practices were suppressed by the Japanese government in the 19th century, contemporary Ainu artists are rediscovering and reviving this sacred art as a form of cultural heritage and resistance.

Chapter III: Tattoo Medicine in Siberia

Frozen in time within the Siberian permafrost, the famous 2,500-year-old Pazyryk mummy discovered in the Altai Mountains was adorned with elaborate tattoos of mythical creatures. These Iron Age designs were not merely decorative. Scholars speculate that the tattoos had medicinal and spiritual functions—functioning as acupuncture guides, charms against illness, and signals of social or spiritual standing. Among various Siberian nomadic tribes, tattooing was closely linked to shamanism. The placement of tattoos on pressure points aligned with the belief that ink could guide spiritual energy flows, an ancient echo of holistic philosophies akin to those found in Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine.

Chapter IV: Filipino Batok and Ancestral Reloading

In the Cordillera mountains of the Philippines, the tradition of batok—hand-tapped tattooing—still survives, thanks to elders like Whang-od Oggay, a nonagenarian Kalinga tattoo artist known as the mambabatok. Historically, batok was part of a warrior’s journey, but it also served as a medium for conversing with ancestors and deities. Patterns symbolized protection in battle, fertility, and tribal affiliation. The ink—a blend of charcoal and sugarcane juice—was seen to carry sacred meaning. Today, the cultural revival of batok is not only reclaiming indigenous art but also reconnecting younger generations with a spiritual vocabulary nearly lost to colonization and religious suppression.

Chapter V: Reclaiming Sacred Skin in the Contemporary Era

Contemporary tattooing borrows from sacred traditions while recontextualizing them in new spiritual and aesthetic frameworks. Around the world, indigenous artists are reclaiming traditional tools, designs, and rituals to heal the ruptures of colonial erasure. In the age of digital connectivity, tattooing becomes a trans-cultural dialogue—a way to reforge community, express spiritual identity, and write oneself into a living lineage. Technologies like digital design and machine tattooing may have altered the process, but the soul of sacred ink endures. As we enter further into a globally connected era, tattoos will likely continue to serve both as a reclaiming of roots and an inked path to the divine.

Conclusion: Body as Shrine

The human body bears stories no book can contain. Sacred tattooing, in its myriad forms and meanings, reveals a universal human impulse: to mark the flesh not for vanity, but to encode the sacred. Whether through Polynesian mana, Ainu spirituality, Siberian shamanism, Filipino myths, or modern reinterpretations, tattoos are vivid reminders that art does not only adorn the world—it sanctifies it, body and soul alike.

Image description:

tatuaje realizado por cristian cordova tattoo del mono chile

License:

CC BY-SA 3.0

Source:

Wikimedia Commons

Useful links: