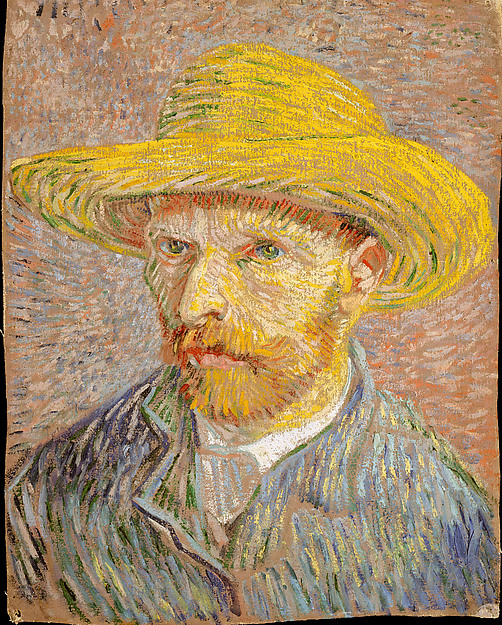

Image title: Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler)

Medium: Oil on canvas

Date: 1887

Source:

The Met Collection

“

We live in a society bloated with data yet starved for wisdom. We’re connected 24/7, yet anxiety, fear, depression and loneliness are at an all-time high. We must course-correct.

”

— Elizabeth Kapu’uwailani Lindsey

Data Canvases: When Painters Collaborate with Coders

Introduction: A New Brushstroke in the Digital Era

What happens when the traditions of oil painting meet the algorithmic structures of big data? In today’s creative frontier, traditional painters are teaming up with data scientists to transcend the canvas. Together, they mine social trends, emotional metadata, and environmental statistics to craft artworks that challenge authorship, reimagine intention, and turn our collective digital behavior into deeply personal visual experiences. These hybrid works often take on a surprisingly poetic quality, where numbers become color fields, tweets become brushstrokes, and machine learning acts as a co-creator.

This article explores the evolving dialogue between traditional visual art and the computational frameworks of data science. Through five key transformations in the history of visual art, we examine how past movements paved the way for today’s cross-disciplinary collaborations, and how technology is steering us toward a radically redefined aesthetic future.

I. From Patronage to Autonomy: Breaking the Historical Frame

The Renaissance marked a period in which art was closely aligned with power structures — religious institutions and royal patrons determined the content, message, and even the materials that artists used. Yet this system, rigid as it was, laid the groundwork for a discourse on authorship and artistic intent. The artist was once a skilled craftsman; by the 18th century, he had become an expressive individual imbued with genius.

This cultural shift set the stage for contemporary questions of agency: Who creates the art? In traditional systems, the artist had final say. Today, in a collaborative project between a painter and a coder, agency becomes diffuse. Data-driven paintings generated from social media feeds or behavioral statistics blur the line between artist, technician, and even audience. In many cases, the ‘creator’ of a visual work might be a dataset drawn from thousands of unknown individuals.

II. Impressionism and Abstraction: The Rise of Emotion and Perception

In the 19th century, Impressionism reoriented visual art from narrative clarity to sensory experience. Later, abstraction would explode that idea, prioritizing inner emotion over external representation. Artists like Kandinsky and Mondrian spoke of universal emotions and spiritual truths encoded within color, line, and form.

Now, data artists revisit this quest for emotional resonance, using sentiment analysis and neural networks to convert emotional data into visual structures. In works by artist-coder duos like Refik Anadol and data painter Laurie Frick, colors correspond to biometric input or social sentiment, such as anxiety levels measured by Twitter posts before elections. Abstract painting, once the domain of the subconscious, is reborn through algorithms that detect and interpret psychological patterns on a mass scale.

III. Conceptual Art and Postmodern Play: The Death of the Author

In the 1960s and 70s, Conceptual Art interrogated the nature of art itself. Artists like Sol LeWitt and Joseph Kosuth emphasized ideas over aesthetics, often hiring others to execute their conceptual visions. Roland Barthes proclaimed the ‘death of the author’, delegitimizing the idea of a singular, intentional creator.

Today’s data-driven art projects advance this critique. With generative algorithms and machine learning variabilities, even the coder’s control may be partial. The role of intention becomes complicated in a system where outcomes are probabilistic. As one painter-coder team described, “We don’t always know how the painting will look until the dataset finishes processing.” In this way, computation acts not just as a tool but as an autonomous agent influencing interpretation and authorship alike.

IV. The Digital Turn: Painting Meets Programming

By the late 20th century, as digital technologies mingled with artistic practices, the idea of collaboration expanded. New media artists like Casey Reas and Zach Lieberman explored interactive installations and data visualization. Yet the merging of traditional oil painting with data analytics is a more recent phenomenon.

In projects like ‘Wikidata Painting’ by Giorgia Lupi and Kelli Anderson, data visualization becomes an aesthetic in its own right. In others, painters use algorithmically generated color palettes derived from climate data, or use AI to simulate brush patterns that respond to real-time urban noise. These works resist clear categorization — they are neither entirely painting nor entirely digital artifact but exist in a liminal space. As such, they forge a new vocabulary for creative practice, inviting engineers to think like poets and artists to interact with systems like programmers.

V. Toward a Posthuman Aesthetic: The Art of Hybrid Intelligence

We now find ourselves entering a posthuman era in aesthetics. Not only does technology shape how we create, but it also alters our understanding of meaning, beauty, and expression. In painter-coder collaborations, the artwork becomes the output of hybrid intelligence — human intuition fused with machine logic.

Philosophically, this echoes questions raised by thinkers like Donna Haraway and Bernard Stiegler: Can a machine feel? Can it create? While AI lacks consciousness, its interpretive structures — trained on vast corpora of human input — enable it to simulate patterns that deeply resonate. When a traditional painter filters these simulations through their practiced hand, the result is an artifact of both minds: the analog and the synthetic.

This shift is not simply technological but ontological. Painting is no longer a purely human endeavor; it has become a collaborative conversation across forms of intelligence. In this, we’re not abandoning tradition — we’re expanding it into territories that Renaissance masters might never have imagined.

Conclusion: Painting the Data Age

Data canvases mark a turning point in art history where the physical act of painting integrates with abstract, often invisible digital processes. These collaborative works challenge our assumptions about creation, labor, aesthetics, and even the nature of visual truth. In doing so, they offer a glimpse into the future of art — one in which humans co-create not only with each other, but with the informational ecosystems that define 21st-century life.

As art becomes more entangled with networks, data sets, and codebases, these painter-coder collaborations might not just reflect the world, but help us reimagine it entirely.

Useful links: