“

Neatness begets order; but from order to taste there is the same difference as from taste to genius, or from love to friendship.

”

— Johann Kaspar Lavater

Tattooed Icons: Body Art as Visual Protest from Polynesia to Punk

Introduction: Skin as Canvas, Skin as Voice

For millennia, the human body has served not only as a vehicle for survival and mobility but also as a living canvas — a stage upon which identity, allegiance, resistance, and memory have been boldly inscribed through the practice of tattooing. Across diverse cultures and epochs, tattoos have transcended their decorative qualities to become acts of protest, spiritual rites, and powerful visual narratives. From the sacred patterns of Polynesian warriors to the gritty iconography of 1970s punk subculture, tattooing has persistently operated at the junction of art, rebellion, and communal identity.

Chapter 1: Polynesian Origins — The Sacred Ink of Lineage and Power

Among the earliest and most elaborate traditions of tattooing is found in the Polynesian islands, particularly in places like Samoa, Tonga, and the Marquesas. These intricate designs, painfully tapped into the skin using bone or shell tools, were not mere ornaments; they were sacred emblems, closely tied to social status, genealogy, and spiritual protection. The word “tattoo” itself is derived from the Polynesian “tatau,” a term echoing the rhythmic tapping sound made during the inking process.

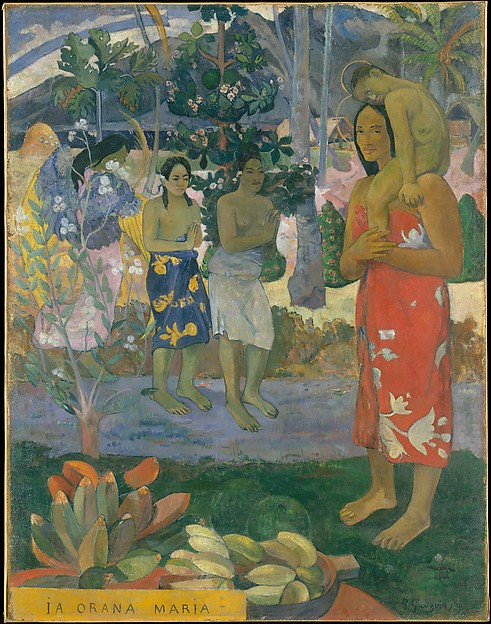

Far from being subversive in their cultural origin, Polynesian tattoos formed a visual language of societal order and ancestral reverence. Yet in the face of European colonization and missionary disapproval, their preservation became an act of cultural resistance. The re-emergence of traditional Polynesian tattooing practices in the 20th century is thus simultaneously an artistic revival and a political assertion of indigenous identity.

Chapter 2: Ink in the East — Spirituality and Class in Japan

In Japan, tattooing developed into a uniquely complex visual language, one that evolved through stark contradictions: from spiritual warding in ancient times to criminal association in the Edo period. Early Japanese tattoos, like those of irezumi, carried spiritual and symbolic meanings, often intended to protect or heal. However, by the 17th century, the Tokugawa shogunate began using tattoos as punishment — branding criminals with visible marks.

In a striking reversal of stigma, members of Japan’s working class and underworld, including the yakuza, adopted full-body tattoos as badges of honor and identity. Using elaborate imagery drawn from folklore and ukiyo-e woodblock prints, artists transformed bodies into spectacles of myth and defiance. These tattoos blur the line between fine art and subculture, anchoring visual storytelling directly onto the skin while resisting conformist social norms.

Chapter 3: Colonial Erasure and Western Reappropriation

The expansion of Western empires in the 18th and 19th centuries brought tattooing into new cultural contexts, often stripping it from its indigenous roots. In European and American societies, tattooing became associated with sailors, criminals, and outsiders. Yet even in this marginalization, tattoos carried stories of pain, camaraderie, and rebellion. Sailors inked anchors and swallows to mark miles traveled and voyages survived — their bodies living maps of a dangerous, unregulated world.

As tattooing slowly gained popularity among elites — including Victorian aristocrats and circus performers — it began to straddle a peculiar space between spectacle and self-expression. Despite the scientific rationalism dominating the era, tattooing persisted as a subversive artifact of the ‘exotic other,’ alternately exoticized, ridiculed, and feared. This tension foreshadowed the modern role of tattoos as expressions of counterculture and resistance.

Chapter 4: The Punk Rebellion — Mixed Ink, Mixed Messages

In the 1970s and ’80s, tattooing exploded as a form of cultural rebellion, closely intertwined with the rise of punk rock. In the wake of social disillusionment, economic crisis, and political conservatism, punk offered a raw, visceral platform for dissent. Tattoos in this context rejected technical precision in favor of urgent symbolism — anarchy signs, skulls, anti-authoritarian slogans, and DIY aesthetics inked onto arms and faces in basement studios and back alleys.

Tattooing within the punk movement was a radical democratization of the body — a painful, permanent middle finger to societal expectations. Unlike earlier tattoos rooted in tradition or spirituality, punk tattoos proclaimed chaotic identity and aggressive visibility. The skin became not only a canvas but a manifesto, asserting, “I am not one of you.”

Chapter 5: Digital Renaissance — Global Connection and New Icons

Today, in the age of Instagram and global subcultures, tattooing has entered a digital renaissance. Machine precision meets ancient symbolism in studios from Berlin to Bangkok, while algorithms surface Maori designs alongside minimalist fine lines. Tattoo artists are now recognized as visual storytellers with international followings, some even exhibiting in art galleries or turning skin designs into NFT-based art pieces. Technologies such as digital stencils and 3D printing have expanded the medium, while cultural conversations about appropriation and authenticity continue to provoke debate.

Simultaneously, tattoos have reclaimed their sacred and political potency. In post-colonial communities, traditional designs honor lost languages and fight historical erasure. Queer and trans communities repurpose ink as rites of passage. The body becomes both archive and altar — bearing personal history and collective memory in lines of ink.

Conclusion: The Eternal Mark

Tattoos are more than art — they are acts of endurance, defiance, legacy, and communion. From Polynesian warriors to post-modern punks, from prisoners to poets, tattooing remains one of humanity’s most profound visual languages. As technologies change and societies shift, the urge to mark the body persists because the body, in its raw vulnerability, always hungers for meaning. In this sense, every tattoo is a miniature protest — against amnesia, against conformity, against silence.

Useful links: